Are we are too fixated on helping our kids succeed as individuals?

The case for ‘civic thriving’ as a new, and better, focus for education

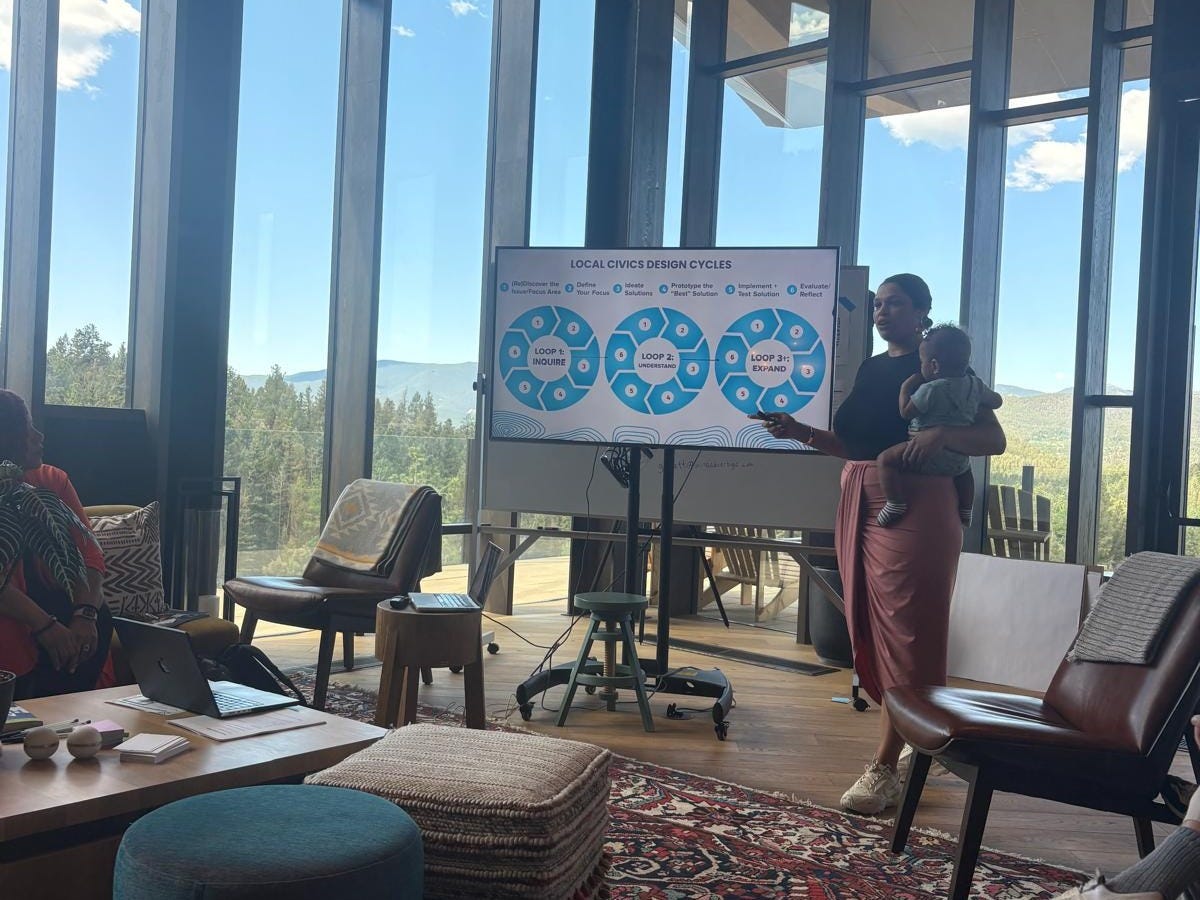

Photo: Jenny Anderson in Colorado

I’ve spent years working on the question of how to help kids thrive. But in recent weeks I have been fascinated by a twist on this question: whether, in our desire to help young people become capable, successful individuals, we have lost sight of the necessity of working towards collective success. How do we orient families, schools and communities toward civic thriving, designing ways for young people to build the world they will inhabit?

Right now, many young people are lonely and distrustful: rocked by wars, a pandemic, a cost of living crisis and deep uncertainty about the future. They distrust civic institutions. Just 10% of Americans aged 18 to 26 (Gen Z) said they have “a lot” of trust in Congress, according to a 2023 Gallup Poll and just 17% trust the Supreme Court. Schools—the public commons for kids—are not trusted as they once were. More than a quarter of kids are chronically absent, and more than 50% of Americans are unhappy with their schools.

Civic knowledge itself is bad—terrible, actually. According to a 2023 survey from Citizens and Scholars, a nonprofit that helps young people build civic skills like having difficult conversations, and collaborating across differences, young adults (18-24) could correctly answer an average of only 1.6 out of four standard civics questions; only 4% answered all four questions right.

But young people aren’t just tuning out because they don’t know enough—they’re tuning out because they don’t believe this system sees them, serves them, or is worthy of their effort. As such, any fix won’t come from better textbooks. It will come from finding ways to encourage civic thriving, rooted in what young people do together, not just what they learn in classrooms. “The question isn’t just what young people need to know, it’s what they need to do and become,” says Daniel Barcay, executive director at the Center for Humane Technology. Democracy is not a spectator sport. It must be practiced: debated, voted on, felt, lost, and won.

Too often in education we assume the fix is more information, which is necessary but by no means sufficient. “Young people aren’t clamoring for civic knowledge,” says Audra Watson, chief of youth civics programs at Citizens and Scholars. “What they are saying they want is ways to engage that are meaningful for them.” In other words: knowing more about democracy will not mean caring more about it. But doing something about it might.

How do you get kids involved in the collective good?

Last week I was part of the team organizing a convening in Colorado that aimed to address exactly this: to broaden how we think about preparing kids for democracy, not just as civics, but as civic thriving. The event included people from the fields of civics, education reform, experiential learning, AI and technology, systems thinking, history and social studies, and school design. There were also folks developing metrics and technology to measure experiences and skills, and yes—civic thriving. Two moms brought babies; three teens helped with very honest feedback.

(I’m not an experienced conference-organiser but Fernande Raine, a friend and the social entrepreneur behind this network-building effort, had asked me to co-host. The book I had just co-written had clearly identified the central problem, she said —kids are disengaged, and often with good reason—and the convening would gather people deeply committed to designing opportunities to help young people get into Explorer mode—ie find pathways to do things they care about, with rigor and support from adults.)

Civic thriving, I learned, is pretty close to human thriving. It just acknowledges that if we factor in the collective, it is good for kids, good for us, and good for democracy. The North Star the group set at the start of the three days was this:

What can we do now to ensure all young people can develop their full potential as individuals who are nurtured in strong relationships, feel connected to a common purpose, and are able to create and contribute in ways that matter to them and their communities?

Redesigning civics for the world we’re living in right now

A new civic operating system cannot be grounded in the ideals of nostalgic humanism (on the left), nor algorithmic nihilism (on the right), argues Kim Smith, founder of LearnerStudio, an education nonprofit.

Instead, it needs to be rooted in what truly helps humans thrive, and designed to co-exist alongside the power and limitations of AI. That will mean having a system underpinned by trusted relationships, incorporating the science of learning, and activating real-world participation. AI will play a role—but one we choose for it, not one designed by technological overlords. It will include networked ways for collective involvement. This will include everyone from educators and museum leaders to youth organizers, clinicians, policymakers, designers and, of course, parents and young people themselves.

Neuroscience shows what great teachers know: learning sticks when it feels purposeful, social, and emotionally resonant. When students work on a real issue in their neighborhood—organizing a food drive, redesigning a park, interviewing elders, or building a game to foster empathy in their school—they are not just “doing civics.” They are becoming civic. They’re rehearsing what it means to show up for the commons, not just striving to advance their place in the sorting game of school. “What did I learn about myself? What did I learn about us? Those are civic questions,” says Susan Rivers, executive director and chief scientist at ithrive Games, a game design studio that is part of the History Co-Lab.

An approach that cares about kids' experiences and feelings is not sentimental. It’s how you raise a generation capable of democracy. Hannah Arendt wrote that the essence of politics is not voting or governing structures—it’s acting in concert with others. Democracy, she wrote, is born when we appear before one another to speak, to act, to be seen.

And yet, we’ve designed schools where that kind of appearance is rare. Instead of spaces of shared action, many schools function as siloed subject systems, often separated from meaning and common purpose.

It also means starting small and getting bigger, recognising that kids need practice at home and at school before they head out to fight for better gifted and talented program policies. “You don’t start with voting or protests. You start with being heard,” said John Dugan, founder of the Center for Expanding Leadership Opportunities.

Moving away from the paradigm of individual success towards “practiced belonging”

Education reformers have been pushing to shift the system from just academic content to also developing skills and competencies. Kids need jobs, eventually, and if we aren’t preparing them for employment, we are failing them.

But in this push to get ready for work, we have largely failed to communicate the importance of public life, or contribution to something beyond self. Even “community-based learning” is often about preparing for employment, not public service (or it’s box checking for college admissions).

Michael Sandel, in a recent podcast with the Center for Humane Technology, argues that our conceptions of freedom, and work, have both been distorted by failing to consider the commons. When we talk about freedom today, he argues, “what we mean really is the freedom to choose our interests…to act on our desires without impediment or with as few impediments as possible.” This is a consumerist conception of freedom, a way to act on one’s full individual desires and preferences.

A civic conception of freedom is different: “My voice matters. I can participate in self-government, I can reason and deliberate with fellow citizens as an equal about what purposes and ends are worthy of us,” he says. This requires a healthy and robust common life, and it imagines work differently. Not just as a way to make money—which is of course important—but also “as a way of enabling everyone to contribute to the common good and to win honor and recognition and respect and esteem for doing so.”

Young people need ways to earn honor and recognition and respect, to practice civics in the commons. Not more lectures about the Constitution, but holding a conversation with someone who disagrees with them, repairing a trail, or revamping a museum exhibit so it doesn’t bore young people to tears. The shift is from passive civics to practiced belonging. From preparing to work as a cog in the machine of democracy to working as a participant whose effort has dignity, and whose contributions are essential to our collective being. “It’s about developing a disposition: I have a role, I have a responsibility. I can ask questions. Civics isn’t a course. It’s a stance,” said Dugan.

Civic thriving requires adults recognize that young people are hungry, and able. That they want to contribute, and we so rarely provide them opportunities to do so. Will they disappoint sometimes? Sure. Not everyone in the workplace nails it every day. Adolescents are emerging: wonderfully raw humans-in-formation, eager both to stand out and fit in, to borrow a phrase from the sociologist Rob Crosnoe. But they are filled with strengths, ideas and energy. They may well want to open text books and study, but they also want to do things in communion with others. “You have to believe young people can change things before you can design like they can,” says the Center for Humane Technology’s Barcay. Give them a messy problem, he insists, and make room for them to solve it.

The network to build this work is in formation and has tremendous energy. Watch this space.

Added Reading:

Fernande Raine and Susan Rivers on the Science of Patriotism in EdWeek.

The knowledge system collapse - Free Press

Is Civics the New Stem? David Bobb

Explorer Mode - EdRe

Thank you for this. Resonated with me especially after having read this article: https://www.nationalreview.com/magazine/2025/10/theres-too-much-doom-and-gloom-in-the-classroom/. That article made me think of your book which is what made me head to your substack where I found this piece. Curious if you're familiar with the work of Jeremy Clifton on primals? (see the article I linked or Google him)

Having taught in England and now living in Finland, I see stark differences in civic education between the two countries (not unexpected), but the difference that has surprised me the most is the entrepreneurship education here. There are far more opportunities to practice entrepreneurial skills, and they are highly valued here, compared to England where I think it’s fair to say entrepreneurial education is almost exclusively available to those with direct connections.

But I also see this and civic education having a different meanings here: service, contributing to society, trust in others and being trusted (Finnish workers have very high autonomy), respect for others’ free time etc.

I was surprised you didn’t explicitly discuss competition/competitiveness wasn’t covered explicitly. Maybe that’s intentional.