What teens need to know in an age of AI

Advice to give your kids right now

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

One of the key arguments we make in The Disengaged Teen is that the number one skill kids will need in an age of AI is being good at learning. Apparently Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google and Alphabet, agrees. "AI will primarily help students who are looking to learn," he told Dan Fitzpatrick, an author and AI expert.

The great divide will not be between those who use AI and those who don’t, but between those who care about getting smarter, digging in, pushing through hard things, grappling with uncertainty and challenging the status quo, and those happy to coast along, resist hard work, or blindly jump through hoops put up for them. The gap will be between those who are motivated and those who aren’t.

In the parlance of our book, the world will reward Explorers and more than those stuck in one of the other three modes (Resister, Achiever, Passenger.)

We spend so much time in education, and probably in our parenting, thinking about what kids need to learn and how to assess it, and not nearly enough time on the fuel it takes to get them to want to do it: motivation. We actually know a lot about what motivates teens. We just don’t design for that, in schools—or at home.

To be very clear, caring about what motivates a teenager does not mean:

Content and knowledge are unimportant. Knowledge is essential: We can’t think critically about nothing. Kids need to create new things based on knowledge of what exists and what can be improved upon. But content and knowledge alone are not sufficient.

Education always has to be entertaining. It is fine to be bored sometimes (here is a really good explanation as to precisely why kids should be bored). Tackling new and unfamiliar things is not all rainbows and butterflies.

Testing isn’t essential. Testing is one of the best ways we have to assess what’s been learned.

Getting good at learning sounds fuzzy, which is why we tried in the book to give it a clear definition. Explorer mode, which we describe as one of the four modes, is where learners have agency: the self-awareness to know what you want, the strategies to go after it, and the ability to adapt when things go off the rails.

This is being good at learning.

Kids in Explorer mode connect their interests to what’s being taught: Can we calculate the potential growth of Beyoncé’s net worth using exponents?

They make suggestions about how to do the work they are asked to complete: Can we work with a partner?

They seek help to investigate things they’re interested in: Can I install and use CAD software on my computer?

They express their preferences: I want to focus on how President Truman grew the government bureaucracy for my history essay.

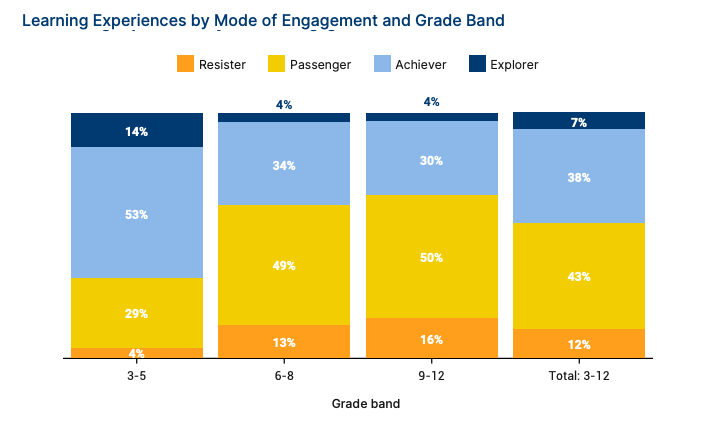

And yet our research—68,000 kids, 2,000 parents, qualitative research with 100 teens over 3 years— shows more than 50 percent of kids are coasting, doing the bare minimum (Passenger mode); plenty of kids are resisting and withdrawing (Resister mode) and a significant minority are in Achiever mode, collecting gold stars for what the system asks of them.

Less than 4 percent of kids in middle and high school get to be in Explorer mode.

Explorer mode for an AI world

AI will exacerbate a lot of this, especially the capacity for kids to get stuck in Passenger mode. So what should parents do?

Tell kids: if the work gets hard keep going

Struggle is where learning happens. Educators call it “productive struggle.”

The “f” word in Silicon valley is friction. Big tech profits by making every facet of life frictionless, from getting your food and taxis to renting your home to reading your emails and summarizing your meetings.

But learning it literally about getting through the friction, not optimising it away.

One way to talk to teens about it could be: Try not to rely on AI before you turn to it. Doing the hard work will build your attention, like running laps before soccer builds your muscles to play better soccer.

Don't judge them, talk to them

Research shows kids are using AI a lot but not talking to parents about it. This is the worst place for parents to be: in the dark. It makes me think of social media in 2012. We thought it would probably be okay. But we failed to account for the incentives: Silicon Valley designed for maximum engagement, i.e. usage, which maximised profits. They didn’t care if the price was our kids’ attention, or longterm mental health.

If your kids are using AI to do their work, remember that cheating wasn’t invented in November 2022. Brains don’t like thinking. We have to train them to do it and to get better at it (as noted above in the point about struggle). Encourage kids to think for themselves. Remind them they want to be able to use AI—not be used by it. And also that AI regularly gets things very wrong.

The message might be: Use AI to test yourself; to make yourself smarter. Use it to figure out the holes in your leaning. Don’t use it to write for you or think for you: that will make you dumber.

School will change, and that might be great

According to a recent New York Times article by Clay Shirky, vice provost of Educational Technologies of New York University, universities are having to rethink how they do things because even the good students aren’t doing the work any more. They are relying on ChatGPT or other LLMs to do the work for them. “If you ask students to use A.I. but critique what it spits out, they can generate the critique with A.I. If you give them A.I. tutors trained only to guide them, they can still use tools that just supply the answers,” he writes.

That means how work is done in school will have to change:

fewer take-home assignments and essays, more in-class essays

more oral examinations

More portfolio assessments, demonstrations of learning and other ways of showing one knows something

More TED-style talks

More presentations

More Socratic discussion without the help of a device thinking for you

All of which will require thinking and learning.

Recommendations:

To read

On being seen and seeing by Julia Freeland Fisher

Rebecca on NPR about how to change the design of schools

On the death of the knowledge system

On the transformation of the classroom (Bloomberg)

To listen to

I loved this Song Exploder with Jia Tolentino on why pop is pure and beautiful (I was mercilessly teased as a teen for loving Tiffany while my friends rocked out to Led Zeppelin. I feel seen.)

How our Brain Learns on the podcast Hidden Brain with Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, whose research featured in our book and who explores meaning-making with teens, including scanning their brains while they do it.

Anything from Coldplay (I went to the concert with my husband and the kids. It was EPIC).

This is clearly top of mind right now in the AI news - parents have been the ones left out of the AI conversation for the past year.

https://fitzyhistory.substack.com/p/what-i-want-parents-to-know-about

This is all good advice - the book looks interesting. I'm sure you're familiar with the Alpha school phenomenon but this is an excellent podcast where motivation is explored in depth.

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/invest-like-the-best-with-patrick-oshaughnessy/id1154105909?i=1000723564395

PS - I think you may know my wife - Megan Barnett.