Why it matters that our teens are bored

Boredom of the right kind can be useful. The wrong kind can be soul-destroying

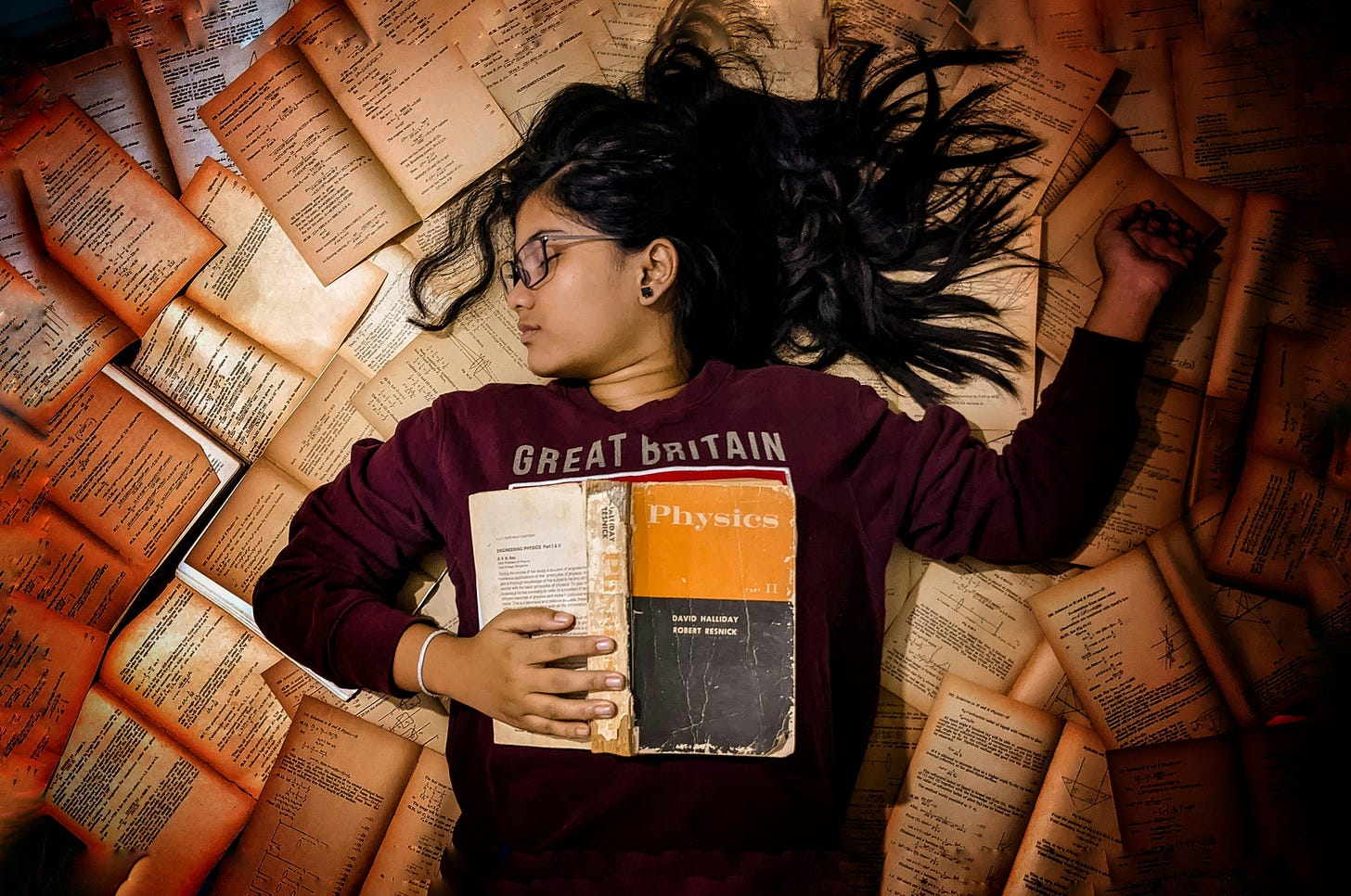

Photo: Sumeet B for Unsplash

The Sunday Times (London) published a big piece on The Disengaged Teen last week entitled “Teens are bored and stressed for four years—Does it Matter?” On the back of the article, the BBC asked me on its Radio 5 morning show to interrogate the issue of boredom, a central theme to our book.

In the run up to the segment one of the producers sent me a quick note summarizing what we’d cover and said, “so being bored is bad, yes?” I wrote back in all caps IT’S NOT THAT SIMPLE. (I am sure he appreciated my all caps flair.)

The virtues of boredom

Actually, some boredom is good for brains.

Firstly, the act of tuning out of external stimuli activates a part of the brain that is critical for creativity: the imagining network, or default mode network (DMN.) This is the reflective, meaning-making area of the brain. It can pull us away from our current context or perspective, and it pushes our consciousness into imagined realities, pasts, and futures, and into the perspectives of others. The DMN lights up when our minds wander or when we daydream, and it helps us contemplate the bigger picture of a situation, connect the dots of the world at large, and generate novel solutions to problems. Kids need to engage the DMN to think creatively.

Mind-wandering, therefore, can be healthy, and developmental scientists worry a lot that kids don’t have enough downtime anymore, due to the fact that many are scheduled to the hilt, while pervasive tech use means many young people don’t really know what boredom is.

Secondly, being bored also forces kids to do something important: figure out how to stave off the negative feelings that come with boredom. Academics call this restructuring. Being bored forces us to think—even subconsciously—what do I want to do? What do I care about? How do I want to spend my time? Academics who study boredom define it as “the aversive state of wanting, but being unable, to engage in satisfying activity.” The opposite of boredom is not being busy; it’s being interested.

The opposite of boredom is not being busy. It’s being interested.

Smartphones and social media are disastrous for restructuring. Rather than face the discomfort of being bored, we pick up our phones and are met with a Xanadu of distractions. Since the tech is built to be addictive, once we’re in, good luck getting out. Many of us probably justify this with things like “I am reading the news” or ‘I am connecting with 50 of my closest friends” (the latter logic being one my daughter uses on me all the time: “I am connecting mom, and you say connection is good”). Brains need downtime. This is especially true of teen brains which are undergoing the mother of all reconstructions and undertaking the epic task of building an identity in the world.

Jenny Odell gave a wonderful lecture about doing nothing, its own form of being bored. “‘Nothing’ is neither a luxury nor a waste of time, but rather a necessary part of meaningful thought and speech,” she said. Being bored helps us build self awareness (what do I want to do, what are my thoughts?) and self regulation (how will I manage these negative bored feelings?) In sum, being bored can be beautiful.

Haven’t teens always been bored in school?

Boredom is fine, when you have agency to do something about it. It can even be useful in a world seemingly defined by maximum productivity and uber optimization. But boredom when you are trapped is different, and much worse. If you are trapped doing something that is stressful, very high stakes, and deeply uninteresting to you, it isn’t just bad: it’s a catalyst for disengagement.

This brings me to GCSEs, that set of exams all British 15 to 16-year-olds take in the months of May and June of Year 11 (10th grade). In my daughter’s case, she will take 26 exams over six weeks, on content she has learned over three years. For Spanish she memorized 80 long questions. For English she has memorized passages from Rebecca and from 12 poems. In all three sciences, she has memorized facts on electromagnetism, genetics and evolution and bioenergetics (I had to look that one up). That’s not mentioning maths, geography and history. Ask any teen right now how they feel about these exams and you will get one answer: “bored.”

I don’t lament that she has exams. Knowledge is essential to learning. Exams are a highly effective way of consolidating knowledge. Some studies even show that they can build intrinsic motivation.

But as in medicine, dosage matters. Kids studying ten subjects, prepping for multiple three-hour exams, all done at least twice in one school year (mock exams and then the actual exams) is not just boring: it’s counterproductive. Boredom here is not just a lack of stimulation or entertainment. It’s a crisis of agency. It’s not a problem of nothing-to-do; but a feeling of helplessness to change things. Students feel this. “Give us time to find our passions,” one teenager told me at a conference organised by the Council of British International Schools this week. “So much of the world has changed,” said another. “The only thing that is sustainable is our will to learn.”

We are not alone in seeing this. The very clever people at OCR — the folks who create GCSEs and A-levels and all sorts of important qualifications —just issued a damning report calling for “less content and more learning.” The “current volume and intensity of exams at GCSE is too high, and an overloaded curriculum is narrowing students’ education,” the awarding body said. Let’s recap this: the folks who literally make their money through selling exams are advocating for more non-exam assessment.

We seem obsessed with kids doing more. But what they need is to care more. Being concerned about kids being bored isn’t coddling them: it’s considering the opportunity costs around how they spend their time. Taking as much information in as humanly possible to spit it out? Or making sense of it, interrogating it, trying to use it to some end?

Here’s what to do

In general:

Encourage your kids toward good boredom: screen-free mind wandering; time we don’t fill with chores and conversations about what else they need to (I know: hard.)

During exams:

Acknowledge their boredom. “It’s hard to do the same material over and over again.”

Explain the upside of exams. Knowledge is critical to learning. They are mastering massive amounts of information. Their brains will build on this knowledge.

Remind them of the critical life skills they are gaining: managing stress; time management; performance under pressure; learning about themselves as a learner. All real world stuff.

Finally, remind them that they matter to you regardless of their grades. Jennifer Brehney Wallace found in her research for Never Enough: When Achievement Culture Becomes Toxic–And What We Can Do About It that more than 70% of young adults thought their parents valued and appreciated them more when they were successful in work and school. More than half said their parents loved them more when they were successful and a staggering one in four believed that achievement, not who they were as people, is what mattered most to parents.

“For many young people, their sense of mattering is so contingent on their performance, and they don’t feel like they can ever perform well enough,” Wallace writes.

Tell them you are in their corner no matter what. And the pain will end. For both of you (though maybe don’t add that last bit.)